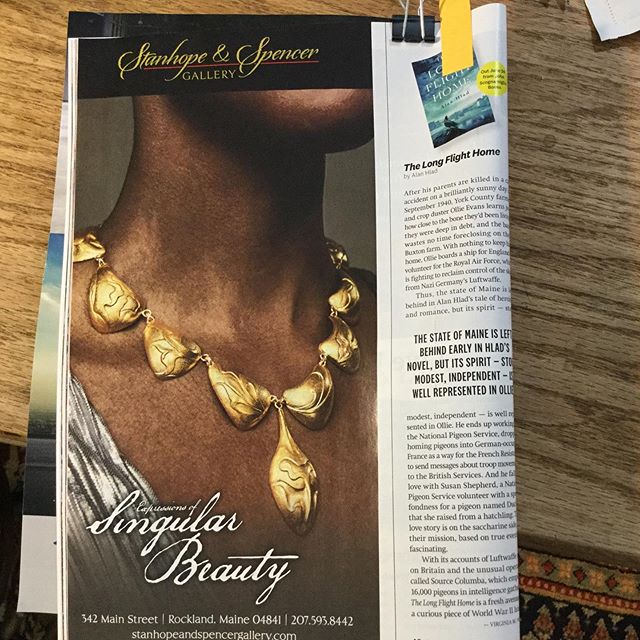

The Art of Henry Spencer

It has been my goal for more than 40 years in the art of Chasing and Repousse to constantly refine my understanding of the infinite light reflecting effects texture and surface planes have on a precious metal. It is only natural for any artist’s body of work, in forty years’ time, to express an affinity toward certain design forms and motifs. However, even when a piece is created through the inspiration of past work, each new piece on my bench is unique, representing not just applied knowledge and experience but also an opportunity to discover and explore new subtle surface finishes via my constant attempts at flawless execution.

Chasing’s advantage allows one to get deeper into the reflective qualities of metal while opening an amazingly broad scope for design exploration, more so than any other direct-to-metal technique I am aware of. The single greatest disadvantage to chasing is time. The amount of time needed to achieve a good piece is extensive with each piece representing substantial commitments of energy and creativity.

If you do understand that rarity and excellence are predictors of value, the price I need to apply to my work becomes understandable, for, not only is each piece the only one in the world, but the time required for each individual effort means the overall number of pieces I will get the chance to complete in my lifetime is limited.

It is with the greatest pleasure that I offer my work to you. I hope you will contact me to discuss adding my work to your collection from work currently available. While I do not custom design work I will always consider informing customers of my latest piece and I can be influenced towards making one form of jewelry or object over another through serious inquiry. Individual classes can also be discussed.

The Art of Repousse and Chasing

What I Do At My Bench

At this stage in my career, I am only concerned with achieving something beautiful. Over the years, I have developed certain primary motifs; design forms familiar to me which serve as markers of development in the art form. The motifs may be repeated; the individual designs never. As a body, my work represents the natural flow of my development, piece by piece; their execution expresses the growth I have experienced.

The nicest thing about spending a little over 47 years developing skills in Repousse and Chasing is having done so. Forty-seven years of experience grants a felicity of access to that single invisible point where the tool meets the metal. My work is about the perfection of an individual strike among thousands to come or thousands before in a moment of unnoticeable time.

Work from my bench represents a culminating moment; time, ability, materials and my artistic sense of their coming together and being “done.” To my eye, every piece I finish expresses within it a moment of perfect beauty. Each tool strike through hours of work, felicity of hand, the metal’s beautiful stringent rules flow through my intention. Any piece I consider done has its point of beauty. Sometimes larger, sometimes smaller, but always complete and unique.

My mentor once

told me that there

are only two lines

in the world,

one is straight

and the

other isn’t.

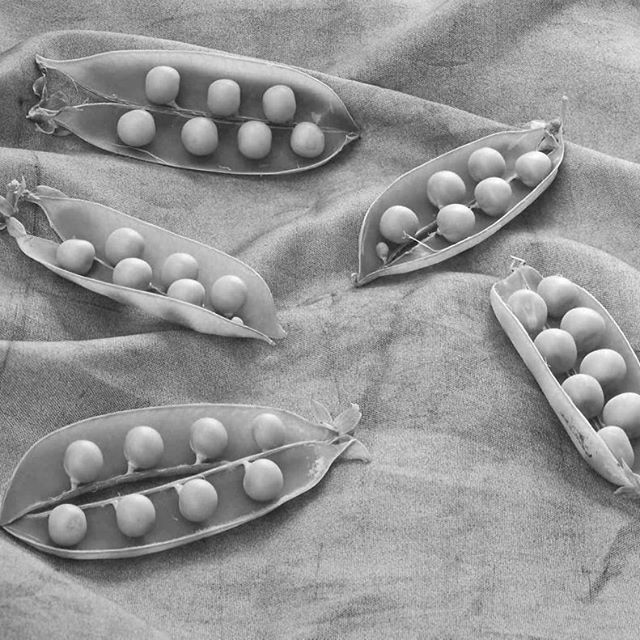

Inspiration of Design

In most cases, the last piece finished is the prime source for the next piece: the evolution of a body of work. My artistic ability is primarily effective in the balance of line and proportion in a limited space. Give me a defined, small area with a line or two drawn through it, and I can join them in a pleasing manner: balance, conjunction and the flow of various design segments within four or fewer square inches. My personal method of achieving this is more akin to free-form jazz than anything else. The only artistic intention is to express beauty in each piece. Other than that, I just do what occurs within the limits of ability. Creating a bunch of controlled volume, I think about this, think about that, and then start doing something. I sketch a lot but almost never a piece I actually make. I find it difficult to relate a two-dimensional pencil sketch into a three-dimensional object. The silhouette of hummingbird or flower is nothing but a line defining one area from another, no different from the squiggle of an abstract line or a geometric curve. In the limited space, one line follows the last, juxtaposed with its predecessor and remaining area in a pleasant manner. In short, I pretty much wing it as I go along, trusting my ability, intuition, and history.

No molds

of any kind

are used,

all work is

free handed.

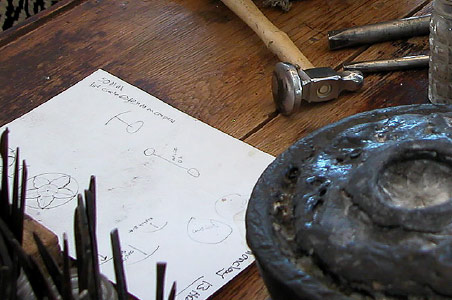

The Process

Starting out with a flat sheet of metal, the artist places it in ‘pitch’ and traces the design onto the metal. Whether done with a pencil or a lining tool,the design elements are transferred to the metal then, from the back of the piece, volume is added. This is Repousse, a French term meaning “to push back,” indicating the process of pushing out the gross shape and details from the back of the piece. Once the overall contour and essential shapes have been established, the piece is turned over in the pitch and the fine detail, surface textures, and various levels are then “Chased” out. The term Chasing is based on the French word “chassuer,” meaning “one who pursues”: in practice, the chaser is tasked with manipulating, or chasing, the created volume into its proper alignment and levels within the desired design and the application of various surface textures to allow the design to stand out. These two steps can easily take up to three to four hours per square inch. A bracelet 1.5 inches wide by 5 inches long is 7.5 square inches or approximately 22 to 34 hours to complete. No molds of any kind are used; all work is free handed.

Chasing Tools

For an artist in metal, the combination of these two techniques – Chasing and Repousse – offers an unparalleled method to create one-of-a-kind works using the simplest of tools: a pitch bowl, a small hammer, and Chasing tools (which are really nothing more than metal rods with specific shapes, angles, and finish on the working end) are all that is needed. However, the drawbacks are substantial, requiring not just significant time in making a single piece but also actual years of practice to become proficient. Of all methods in metal smithing, Repousse and Chasing, for me, has been the most satisfying and the most difficult process to master. I can think of no other skill in smithing that offers more in the way of either challenge or results.

These techniques

offer unparalleled

method to create

only one in the

world works using

the simplest of tools.

Gold Versus Silver

I work in 22k gold, sterling and fine silver. Other than the cost of the metal with gold being 45 times more costly than silver, the biggest difference between them is silver’s ability to be oxidized. Oxidizing sterling silver allows the artist to color the metal with a patina. The patina accents the intentional difference in surface textures and details and allows subtlety to stand out. High karat 22k gold will not oxidize, thus subtle differences in surface textures are lost to the eye. The artist needs to exaggerate the textures, design separation and other details to make them visible to the viewer. With both metals, refined detail can be lost in the overall inherent shine. Oxidizing silver fights this loss. With gold, stronger textures and deeper separating lines are needed to compensate for metallic shine. In short, silver’s oxidizing properties allow the artist to use a lighter hand; gold needs more force with the hammer to expose the intended design.

There is really no difference in what can be accomplished with either sterling or gold. Silver requires more annealing (the softening of metal through heating and quenching). Being much softer, gold needs much less annealing but has far less inherent strength; consideration needs to be given to the actual structural values within the piece which can limit – not what can be done but what can work – in a piece of jewelry or other chased object.

I admit to an aesthetic preference for sterling silver. Minute detail can be made to jump out and become a primary focus point; it reflects pure unaffected light back at the viewer and can pick up and display colors from what it’s reflecting. Gold is always gold; it can reflect back colors but it always adds its own stamp. Gold is a valuable metal; silver is noble. Both are a pleasure to work with and have their own rules to achieve desired effects and results.

The finishes on

my work are

accomplished

intentionally.

Cost Structure

The full expression of my artistic abilities learned over 53 years at the bench and more than 45 years developing skills in Repousse and Chasing means I spend a minimum of six to eight hours per square inch. Some pieces I now make can take as many as twelve hours in the same square inch.That is just the time spent Chasing a piece. There is also the time spent designing and basic metalsmithing to turn the work into something that can be used. As necessary as is the time spent on Repousse, Chasing, and construction, there is also the intense degree of concentration required to meet my personal criteria for achieving excellence rather than simple acceptability. Each piece also represents exhaustion of mind. It actually takes time to “get out of,”the last piece prior to starting the next one. All of this means that the body of my work grows very, very slowly. I see value as a combination of quality and rarity. All of my pieces are one of a kind; each the only one in the world. Realizing this at the bench takes time and effort; my commitment to achieving perfection leads to rarity. The prices on my work are a function of all this. Skill and experience leads to beauty and limited production, time and material costs lead to price.

A word about patinas

I use a very diluted solution of Liver of Sulfur applied under hot running water allowing me to establish hues of blues and reds. These tones are only stable in the deepest recessed areas and strongest finishes. The ability to oxidize silver to a controlled patina is an essential aspect of my work in this metal. The finishes on my work are accomplished intentionally. It has been my experience that the colors will remain true as long as no chemical cleaners are applied. The best way to polish a piece of my work is with a soft napless rag and a bit of the moisture God gave you.

Care and feeding

Both Sterling Silver and 22k Gold are soft metals. Any vigorous rubbing will eventually diminish fine detail by actually stripping away surface metal. In all cases, a light hand is what is needed.

When polishing a piece of my silver work, please do not ever use any kind of paste or liquid silver polish. Doing so will result in a drastic alteration of the patina on the piece, which will change its “look” entirely. A jeweler’s cloth polishing rag works well, but the best method is a soft napless rag with a bit of the moisture God gave you. The term “spit and polish” works here. This “old fashion” way does take a bit of time, but the damage done to very fine detail and patina is almost nil.

Polishing 22k gold should almost never be needed. 22k does not tarnish to any degree, but a bit of soft, soft, rubbing with a damp cloth will brighten the piece up a bit. Other than that, there really isn’t anything you need to do. Particularly with 22k gold, the need for a soft hand is paramount. When I am touching up a piece in inventory, I use a bit of old dampened flannel and spend no more than two minutes lightly rubbing the piece.